In the mind of Maryam Touzani

Inspiring works, ideas and places

A movie ? A special day, Ettore Scola

A book ? The Stranger, Albert Camus

A painting – An artist ? Caravaggio

An instrument ? The violin (ill. : Hakim Alakel)

A song ? Losing my religion, R.E.M

A dish ? Spaghetti alla vongole

A place ? Tangier

Interview with Maryam Touzani

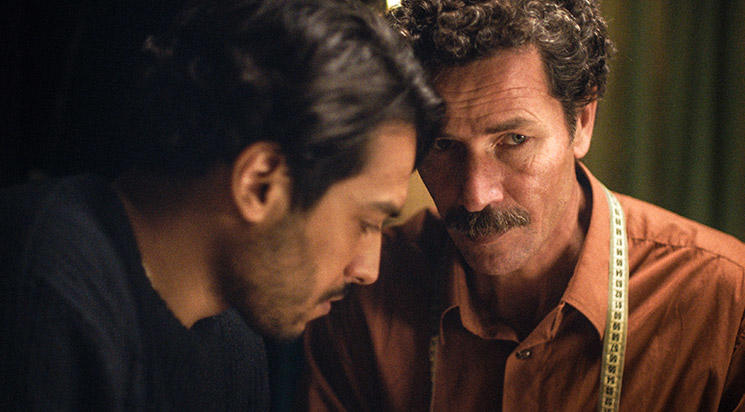

Director of Bleu du Caftan

In theaters March 22, 2023

During our stay in Morocco, we had the chance to interview the talented filmmaker Maryam Touzani (Adam, Un certain regard Cannes 2019) at the Villa Zevaco, a listed 20th century historical monument in Casablanca.

With an open heart, Maryam Touzani looks back on her career, shares her memories as well as her thoughts on cinema and the need to enhance the Moroccan cultural heritage through her films.

This meeting was also an opportunity to discuss her new film : Le Bleu du Caftan, which we were able to preview at the Marrakech International Film Festival, and which will be released in France on March 22, 2023.

- Hello Maryam ! You were born in Morocco, in Tangier, then studied journalism in England. You then returned to live in Morocco as a journalist. Why was it important for you to return to your native country ?

I am very attached to Morocco, I feel very Moroccan. There is a part of me that is Spanish on my mother’s side, but I was born and raised in Morocco. I love Morocco, it is a country that I am passionate about and for which I have a very strong attachment. I have traveled a lot abroad, but Morocco has so many wonderful things to offer that I wanted to build my life here, at home.

- So you started your career as a journalist. How did cinema come into your life ?

I love discovering other people’s worlds and listening to their stories. That’s how I became a journalist, it was a way for me to give a voice to stories that touched me. I had never imagined that one day I would become a director, but the death of my father was a turning point. That’s when I wrote my first short fiction film, « When they sleep« , released in 2011.

I needed to talk about certain things, particularly related to death and the way we live with death in society. Things that I felt in my own flesh and that I needed to let out. So I wrote this short film spontaneously, without telling myself that it would necessarily become a film. I just needed to write it and I couldn’t tell what I felt through a documentary, because it was a feeling, I needed to tell it through a fiction.

As I had not done any fiction before, I wondered if I was really capable of directing one. At the time, my husband (French-Moroccan director Nabil Ayouch) encouraged me to do it after reading the script. He told me : « If it’s something you feel deeply inside, follow your instinct, don’t be afraid, do it !«

So I made that first short film. It was very beautiful, because I felt that I shared something with my father. It was a way of mourning, and it was also a real discovery with cinema. But after this first short film, for me it stopped there, I did not want to make a film. However, everyone said to me : « So, when is the second short film ? » And I always answered : « But I’m not going to make a second short film » ! (laughs)

I didn’t make a film for five years, until I felt the desire again to make a second short film called « Aya va à la plage« , released in 2015. In the meantime, I had spent a lot of time with Nabil on the sets of his films, especially on Much Loved (2015). I followed the whole writing process, the casting, and then the shooting. So I learned a lot with him, and my second short film may also have been born from this experience spent on the sets with Nabil.

After my two short films, I was told again : « When is the first feature film ? » I didn’t know if I wanted to make a first feature film ! But again, I felt that it was life that was leading me towards things. My first feature film « Adam« , out in 2019, is tied to a personal story. Most notably, it was my own pregnancy that sparked my desire to make this film.

- The journalist’s task is to show a reality and to expose facts in an objective and neutral way. Has this influenced your cinematographic approach ?

I wouldn’t say it’s neutral. In any case, in my feeling, journalism was born from my interest in the stories of others. What I am passionate about is the human being above all. And here, it was like an encounter where the image was added. Before, I was writing with words, and little by little I found myself thinking in images, with sounds. It was as if it added a dimension to a desire that was there and that was expressed through words. When I first started writing my scripts, it was very visual : colors, textures, everything is very present.

Morocco & cinema

- The first film that made an impression on you ?

It is the film « Ali Zaoua, prince of the street« , by Nabil Ayouch, released in 2001. The first time I saw this film, I was a student in Madrid, and I came across it by chance on television. It was the first Moroccan film I had seen, and I was stunned. It was a real slap in the face because I had never seen Moroccan films like that, and I didn’t think that Moroccan films like that existed. It was the first time I had seen something that was so real. It was also overwhelming because I felt like there was a whole Morocco that I didn’t know, that I didn’t understand. I think that it fueled this desire to go towards the other, but also to go towards things that I did not know and to leave my comfort zone.

I know that this film had an impact on me without me knowing it at the time. The funny thing is that I didn’t know Nabil when I saw the film. At the time, I was upset by it, but I didn’t remember the name of the director. It was later, when I worked as a journalist and wrote about cinema, that I made the connection between Nabil and this film, the day I had to interview him.

I saw the film again in preview two days ago, here in Casablanca, because it was re-released in theaters in a remastered version. It’s incredible how masterful this film is. I had a lump in my throat. That’s when I also understood the power that a film can have. A film can help change realities, and make people aware of certain things. I didn’t know about social cinema and even less about Moroccan committed cinema, and there I understood how vital it was to make films like that.

These street children in the film Ali Zaoua are invisible to people, and that is what is painful, because by dint of seeing them, people no longer see them. With this film, Nabil made people look at them, listen to them, live with them, and feel what they feel. He spent two and a half years with them, walking the streets of Casablanca. It was an extremely difficult shoot, as you can imagine. I don’t know how he managed to make such a film…

- Tell us about your favorite childhood cinemas and the ones you go to now !

When I was little, I used to go to a cinema in Tangier called Le Paris, and then as I grew up, I used to go to the Cinéma Rif. I think that they have made this place something very beautiful. I love what it has become, all the youth it attracts, the interest it arouses. There was a real lack at that level, and it’s a real intellectual meeting place too, so it’s a stimulating place. The youth of Tangier was in need of places like this, so I’m delighted.

- There are a considerable number of cinemas in Morocco that have closed. Why do you think this has happened ?

There was a time when there were a lot of movie theaters, but then they started to close. Hollywood movies, like everywhere, took over, and the small theaters couldn’t afford to have recent movies, so they offered old movies, but nobody was interested.

There was also a real problem with piracy. Then Bollywood cinema, Egyptian cinema, or big blockbusters gradually got the better of these cinemas.

But there is a will to revive these theaters. I don’t know how it will end, but for a country of more than forty million people, the number of cinema screens is so small and tiny… That’s what makes things a bit complicated for filmmakers here, because when the films come out, there aren’t enough theaters for the industry to develop.

- It is no longer in the culture or in the habit of Moroccans to go to the movies ?

Totally, it’s also a cultural problem. It’s something that’s not embedded enough in the culture. When my mother was young, she used to tell me that she used to go to the movies with her parents, but at some point this practice stopped. There is work to be done on this level, but today it is more complicated, because with platforms like Netflix, the challenge becomes even greater.

Last night, at the premiere of Ali Zaoua, there were many people because there was a great expectation. It is a film that has really marked the Moroccan imagination. The younger generation has not necessarily seen the film, but everyone knows it or has heard of it. It’s great to show it again in theaters because it’s a way to rediscover the film and interact with the public. It’s also a way to ask « What’s the balance after twenty years ?« . In the end, things haven’t changed that much, we’re facing the same issues…

- What are the film festivals in Morocco that you like ?

There are many interesting film festivals in Morocco, such as the Tangier National Film Festival, the Marrakech International Film Festival, the Rabat International Auteur Film Festival, and the Salé International Women’s Film Festival. What is good in Morocco is that we encourage these cultural events around the cinema. We are spoiled in Morocco, there are excellent film and music festivals all year long !

Women & Cinema in Morocco

- What is the place of women filmmakers in the Moroccan audiovisual landscape ? Is it a place that is being renewed ?

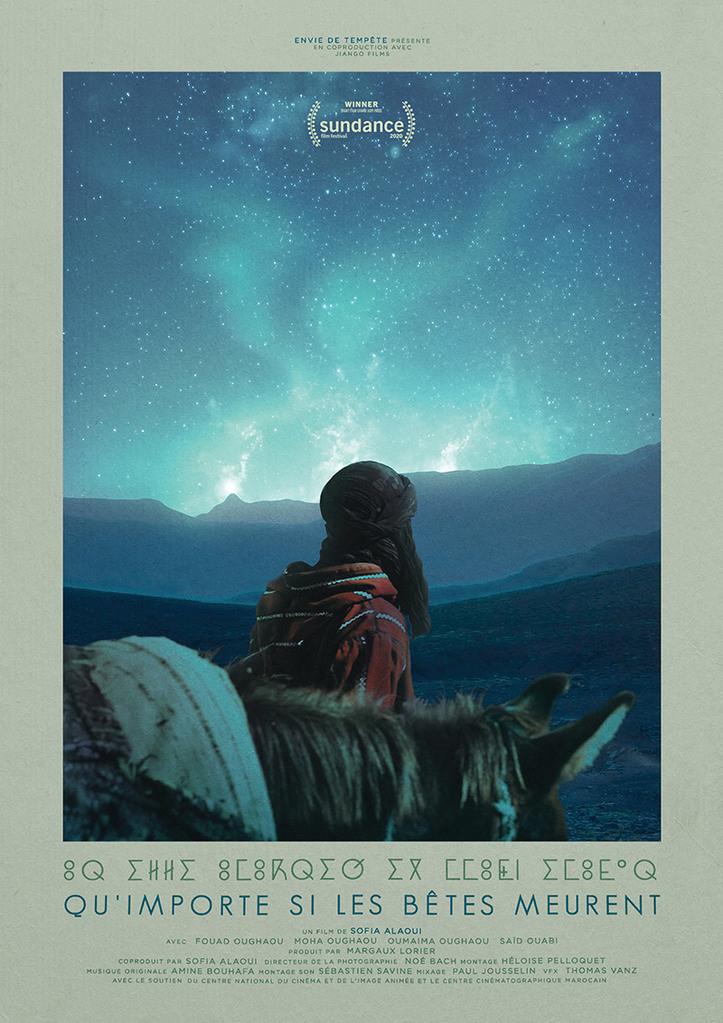

It’s dynamic, there are new Moroccan directors, such as Sofia Alaoui whose short film « Qu’importe si les bêtes meurent » (2021) won the best Cesar award, or Yasmine Benkiran and her film « Queens » (2022) which was at the Venice Critics’ Week, as well as at the Marrakech International Film Festival. There are young Moroccan directors here whose films cross borders, it is on the move !

- So you are not alone ?

I don’t feel alone no, and then what I always say is that I’ve never had any problems making films as a woman. I’ve never felt that I had less opportunities to make a film because I’m a woman. I’m often asked that question, but no it’s not, and it never has been. I haven’t had fewer opportunities to get financing, nor have I had problems on my shoots just because I am a woman.

- Who are the women filmmakers in the Arab world whose work you like?

I don’t like to think of myself as a female filmmaker, or to talk about male or female cinema, because it’s as if it locks me into a category. I like to talk about cinema at all, and sometimes I wish I didn’t even know if it was a man or a woman who directed a film.

For example, when I made my first feature film Adam, I got a lot of questions about Adam being a woman’s film. Yes, it is in the sense that I am a woman, I directed it, and there are two strong female characters and a little girl, but some people went so far as to ask me « Why is the child that is born a boy and not a girl ? » or « How come the male character is so nice ? » He is nice, because there are nice men !

I don’t want to feed this way of thinking, and to be asked again : « Is your next film also going to be a woman’s film about women’s issues ? » Well, not necessarily, what interests me is the human being, and the human being is masculine, feminine, asexual… it is full of nuances.

Le Bleu du Caftan : inspirations & Moroccan heritage

Synopsis : Halim has been married for a long time to Mina, with whom he runs a traditional caftan store in the medina of Salé, Morocco. The couple has always lived with Halim’s secret : his homosexuality, which he has learned to keep quiet. Mina’s illness and the arrival of a young apprentice will upset this balance. United in their love, each will help the other to face his fears.

- Can you explain how the idea for your new film Le Bleu du Caftan came about ?

It all started during the location scouting for my film Adam. I met a man in the medina who touched me a lot, because I felt that there was a whole part of his life that he was hiding, because society wouldn’t accept it. Maybe that wasn’t the case, and that was just my feeling, but I felt that very strongly. I went back to see him several times, I spent a lot of time with him. I realized that he had brought back memories of many men I had seen from afar in my childhood and teenage years, or stories I had heard in hushed tones, of couples who were together but whose husbands were gay. When I met this man, it was perhaps purely a feeling, but it brought me back to all that. This character was then built in me.

In the film, the character of Halim is also a master craftsman who is trying to keep alive a trade that is dying. There are less and less master craftsmen unfortunately, and their know-how is dying with them. This is something that touches me deeply.

I grew up with one of my mother’s caftan, the one I wore to the Cannes Film Festival. This caftan marked my childhood and my adolescence until the day she gave it to me. The day I wore it, I understood the value of these things, and the beauty of being able to transmit them. Especially today, in a world where everything goes too fast and we don’t appreciate these things anymore.

So I spent a lot of time with master craftsmen in Casablanca to listen to them and understand their feelings about what is happening in their environment. When I write, it’s never a thoughtful writing, I never think beforehand about my characters and I don’t ask myself : « What story will I write ? »

It’s always encounters with people or places that inspire me and that, little by little, will make their way inside me. One day, I feel the need to write, and that a story has been built somewhere without my knowledge. My characters appear, and it’s as if they’re holding my hand and saying, « Come on, you’re going to do this with us. » When I write, it’s almost like automatic writing. It’s really very instinctive.

- In your films, you often highlight the idea of transmission, as well as the Moroccan cultural heritage : Moroccan pastry in Adam, craft of clothing in Le bleu du caftan. You have also shot all your films in the heart of the medina of Casablanca. Are these themes and places close to your heart ?

There are a lot of things that we forget in our modern world and leave behind. Maybe I’m nostalgic or romantic, but these are things that touch me a lot. I want, if only for two hours, to shed light on them and to make people aware of them too. Of course, there are things that need to be shaken up in the tradition, but there are also traditions that are beautiful, and that need to be protected because they are part of who we are. I want to be able to tell them differently in the films, to sublimate them, and to value them. The tradition of the maalem (master craftsman) is precisely a tradition that is disappearing, and this was difficult for the shooting. For my two films, I found myself facing real problems.

When I was going to shoot Adam, I went around the medina to find rziza (Moroccan pastry), prepared by hand and not by machine, but I did not find a single person… And for the maalem, it’s the same ! I went around the medina, I asked everyone I knew but apparently all the maalem have left the medina.

Some work in designer workshops, others have dispersed, and there are also those who work only with the machine because that’s what works, it’s faster and cheaper to do. The problem is that the machines all tend to do a very similar job. To know if a caftan was made by hand or by machine, you have to turn it over.

It is a shadow profession that is no longer transmitted, because these artisans no longer find apprentices. Young people today want to do a job where they will earn money quickly. We live in a world where everything goes very fast, we see it with the fast fashion industry where everything is disposable.

But my mother’s caftan has stood the test of time because it was made in a meticulous way. I don’t have a daughter, but I have a son, who may give it to his own daughter or wife. An artisan takes months to design a caftan, his very soul depicted on what he is making. It is a work of art, a jewel.

Maryam Touzani’s recommendations in Casablanca

Where to see a movie ? The Lutetia movie theater

Where to eat ? Dar Dedda and La Squala

Where to walk ? Getting lost in the medina

A place of well-being ? Near the sea, along the cornice

Where to drink a tea ? The Imperial in the Habous district

Another place ? The bookshops in the Habous district