For more than 150 years, from the 11th to the 13th century, a politico-religious group settled in the north of Iran, in a network of impregnable fortresses, fought against the foreign hold of the Turks established throughout the region. Called Assassins, Ismailis, Nizarites, heretics or hashishins, these dissidents of Shi’ism managed, despite their small numbers, to instill fear among the crowned heads and highest enemy representatives.

If the expression « sect of the Assassins » is often evocative, the fortress of Alamut, the headquarters of the sect at its peak, on the other hand, is relatively less known. However, by its astonishing location, its centuries-old history and the many legends that surround it, Alamut constitutes a timeless place, which summons the East and the West.

ALAMUT : HISTORY, POLITICS & RELIGION

The Alamut Fortress, a stone construction of 20,000 square meters, is located in the north of present-day Iran, not far from the Caspian Sea, and culminates at more than 2000 meters above sea level on a rocky peak. The origins of the construction of the Alamut fortress are not certain, but it is likely that the « first » fortress was built in the 9th century, by a ruler of the region.

In the 11th century, the arrival of the Seljuk Turkish dynasties, which quickly converted to Sunnism while the population was predominantly Shiite, caused great political, religious and social upheavals in the region.

The history of the fortress of Alamut is inseparable from the figure of Hassan Sabbâh (1050/70 – 1124) ; he is, in fact, the instigator of a project whose main goal was to fight against this Turkish Seljuk power. Around 1090, Hassan Sabbâh decided to invest a fortress reputed to be impregnable, Alamut, which from then on constituted the center of his authority. He thus gradually became the leader of a politico-religious group, and established a military and ideological strategy.

It is necessary to specify the religious environment in which Sabbâh evolves : the Assassins are indeed Nizarite Ismaelis, one of the obediences of Shiite Islam. Ismailism is a faith in which the figure of the Imams is central, and embodies the support of a particular ardor. Ismailis are distinguished by their esoteric reading and vision of the Qur’an ; according to them, the Qur’an contains hidden messages and knowledge, understandable only by certain people, the initiates. It is thus a mystical, intellectual and philosophical current, which advocates knowledge and promotes exaltation through the possibility of access to « secret » knowledge.

Knowing that he was at a disadvantage in terms of numbers in the fight against the Seljuk, Hassan Sabbâh then imagined an innovative mode of struggle : after training elite soldiers, the fedayeen, later named assassins, he sent them to commit the murders he had precisely prepared, designating the target to be hit.

These murders perpetrated by the Assassins are thus aimed at two categories of targets : political figures – princes, ministers, etc. – and religious figures, the vast majority of these victims being Sunnis. In 1092, the Nizarites committed their first large-scale attack on the powerful Seljuk vizier, Nizam al-Molk.

Little by little, Hassan Sabbâh extended his influence, and conversions to Ismaelism multiplied in reaction to the Seljuk, creating what is sometimes considered as a small Nizarite « state », composed of a network of several fortresses in addition to Alamut. At the beginning of the 12th century indeed, Hassan Sabbâh sent some of his followers to present-day Syria. This branch of the Nizarites also established itself in fortresses, Masyaf being the most important.

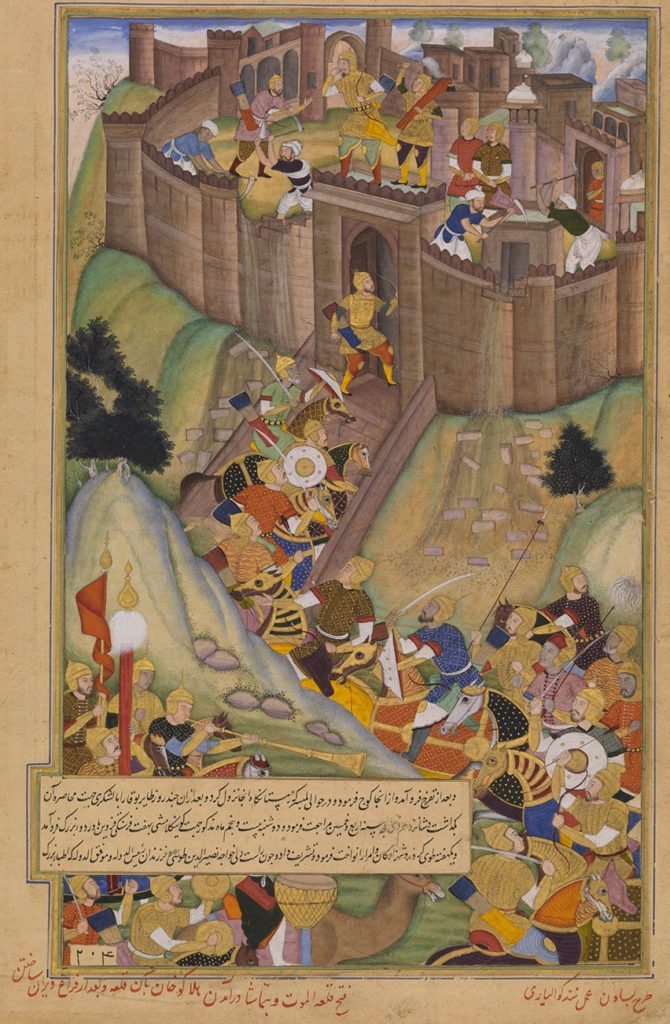

The history of the Assassins in Alamut, and more generally in Persia, ended with the devastating arrival of the Mongols ; guided by Hulagu Khan, grandson of Genghis Khan, they seized every Ismaili fortress, and Alamut is thus destroyed and razed to the ground for the most part in 1256.

The demolition of the fortress by Hulagu Khan. Watercolor and ink on paper, circa 1596. © Virginia Museum of Fine Arts

If the Assassins in Syria remained active, the communities in Persia were dispersed. Nizarite Ismailism, however, continued to spread, often under the guise of Sufism, and the line of imams continued. Since the 19th century, the Imam of the Ismaili people has been embodied in the peaceful person of the Aga Khan.

GENESIS OF THE LEGEND OF THE ASSASSINS

Legend is a more than recurring term when we look at the history of Alamut and these men « in love with death« , in the words of the writer Vladimir Bartol. Having voluntarily surrounded themselves with secrets about their way of life and their organization, the Assassins thus quickly gave birth, from their time and until today, to numerous stories, chronicles, myths, or novels, in which historical reality and fantasy imagination are intertwined.

According to the adage, history is written by the winners ; indeed, very few sources internal to the sect are known, due to the almost total destruction of Alamut during the Mongolian raid. The testimonies that we possess are thus written mainly by the enemies of the sect, namely Sunni authors. These authors, eager to fight politically and ideologically against these « heretics », are thus at the origin of a « black legend » about them.

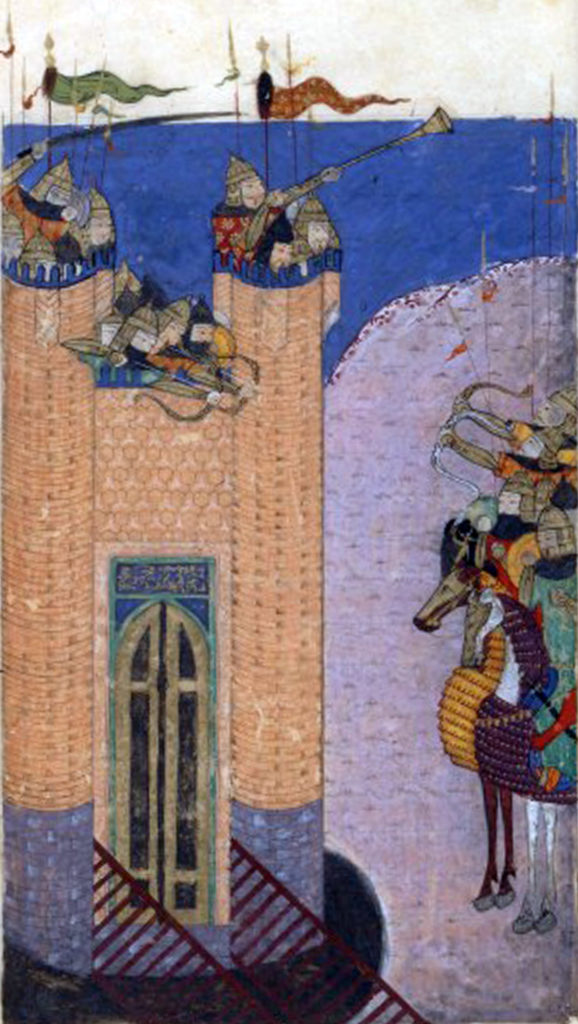

The attack of Alamut.

Tarikh-i Jahangushay-i Juvaini, 1438 © BNF

But quickly, the rumors around the existence of the sect did not remain local, and spread in Europe, in particular thanks to chroniclers such as Guillaume de Tyr (1130 – 1185), one of the greatest historians of the time of the crusades ; it is in his writings that one of the first mentions of the term « Assassins » appeared.

However, the most resounding echo story is undoubtedly Marco Polo‘s Book of the Marvels of the World, written in 1298 by Rustichello of Pisa. When Marco Polo crossed Persia, probably in 1273, Alamut had already been destroyed by the Mongols. However, he relates the customs of the Assassins as if they were still active, presumably by collecting the stories that still circulate in the region.

He tells how Hassan Sabbâh would have created at the foot of Alamut a set of marvelous gardens, a true « paradise » on earth offering food, lush vegetation and young women, and intended for young Assassins who could stay there for a while. Drugged with hashish according to the story, the young men thought they were in the true Paradise dedicated to the martyrs of Islam. Once the effect of the drug had worn off, and back to reality, their only desire was to return to Paradise. Thus, at the first word of Hassan Sabbâh, they committed the requested assassination, knowing that the outcome would be a certain death, and happy to have the certainty of returning to Paradise.

THE MYTH’S APPROPRIATION BY CULTURE

The 20th century marks a turning point in the blossoming of the legend of Alamut. Finding in the West a particularly favorable ground for its diffusion, the myth of the Assassins becomes a frequent reference in the culture. All these sources then influenced each other, relayed the story and fed the legend in turn.

It is in literary circles that references to the fortress first multiplied ; we can mention in particular the novel Alamut by the Slovenian author Vladimir Bartol (1903 – 1967), published in 1938. The story takes place when Hassan Sabbâh is already settled in Alamut, and devotes himself to the training of his group of elite soldiers. Bartol’s inspiration from the writings of Marco Polo is very marked, because he takes up the idea that soldiers are introduced into an artificial paradise, under the influence of hashish, and want to return there by any means when they wake up.

Bartol, through this literary ruse, addresses a veritable denunciation of the political situation of his time in Europe, which saw the emergence of the authoritarian regimes of Fascist Italy, Nazi Germany and the USSR.

The strength of any organization rests on the blindness of its supporters. People occupy different ranks, depending on their ability to manipulate ideas. […] That is why I divide humanity into two fundamentally different categories : a handful of people who know what the realities are and the vast majority who do not. What else do they have left but to gorge themselves on tales and legends ?

Hassan Sabbâh, in « Alamut » by Vladimir Bartol (1938)

More recently, many other authors continue to be inspired by the story of Alamut and its emblematic protagonist, Hassan Sabbâh. Amin Maalouf, a Franco-Lebanese author, for example, chooses to immerse us, through his novel Samarkand (1983), into the story of the genesis of the fortress. He centers his story on the Persian poet Omar Khayyam, who, according to certain legends, would have befriended Hassan Sabbâh and the future vizier Nizam al-Molk during his training. Through this dreamlike aspect of history, Amin Maalouf proposes a political as well as a personal reflection on questions of faith and the search for happiness.

The legend of the Assassins truly penetrates all areas of « popular » culture, in the sense of being accessible to the greatest number. For example, the renowned French rap group IAM mentions Alamut in their song « La fin de leur monde » (The end of their world), and the international platform Netflix has sailed on the appeal of this historical period through the Marco Polo series, in which the protagonist is brought to a completely imagined meeting with the leader of the Assassins.

However, perhaps the most striking echo of the Alamut myth is the one operated through video games. If the Prince of Persia series of games began in the 1990s to develop a taste for the Persian imagination and Persian settings, the Assassin’s Creed games are those that provoke, or at least renew, a huge interest in the sect. The first game of the series, launched in 2007 by Ubisoft, was directly inspired by the sect of the Assassins and its imaginary world.

In particular, the game takes up the famous credo whose belonging is attributed to the Assassins in an uncertain manner : « Nothing is true, everything is allowed« , and which also opens Bartol’s novel. Through these words are perpetuated some of the fundamental elements of the Assassins’ legend, such as not choosing civilians as targets, or mastering the art of disguise in order to blend in with the crowd and reach his victim.

On the other hand, the setting of the game is not Persia or the fortress of Alamut ; the action takes place in Syria, while mixing elements specific to the birth of the sect in Alamut.

THE EMBODIMENT OF A CERTAIN UNIVERSAL IDEAL

Why have the Assassins fascinated so much since the beginning of their existence ? For some, they embody devotion to a right cause, fighting against an enemy and unwelcome authority. Assassins show an undeniable moral rigor, although used for dark purposes, to say the least. The murders committed by the sect are indeed not random ; the targets being exclusively of high political or religious affiliation, and therefore never civilians, the Assassins assume in the eyes of some the role of protective vigilantes of the population.

To these moral qualities are added « physical » qualities. In order to carry out their missions, Assassins demonstrate great dexterity, both in the expert handling of weapons and in the art of disguise, but also great agility in order to enter guarded areas – reflecting the attractive quest for mastery of one’s body as well as one’s mind.

Finally, the idea that with a handful of men, highly trained, fully dedicated and acting in the shadows, it is possible to overthrow the greatest empires and touch the highest people, is also very strong.

This is also linked to the timeless character of man’s revolt against oppressors and a struggle for freedom, both external and internal. Both in the narratives and in the current adaptations, the existential dimension is very present, and the Assassins’ presumed motto, « Nothing is true, everything is allowed« , by its nihilistic vision of the world, seems to gather more and more followers today.

We visited the Alamut site in 2019. Clémence wrote her Master’s thesis on this site, under the title « The Assassins and the fortress of Alamut in Iran : history, myths and tourism issues« . If you have any questions, or if you want to know more, please do not hesitate to contact us !

• • • To stay in the atmosphere of the time • • •

Amin MAALOUF. Samarkand. 1989.

Vladimir BARTOL. Alamut. 1938.

Omar KHAYYAM. The Rubâ’iyat. XIe-XIIe siècles.

Video game Assassin’s Creed, 2007.

Alamut valley © Shaun Busuttil

Non-exhaustive bibliography

• DAFTARY, Farhad. The Assassin Legends : Myths of the Isma’ilis. 1994.

• DAFTARY, Farhad. A Short History of the Ismailis : Traditions of a Muslim Community. 1998.

• LEWIS, Bernard. The Assassins: A Radical Sect in Islam. 1967.