SYNOPSIS OF THE MOVIE THE TASTE OF CHERRY

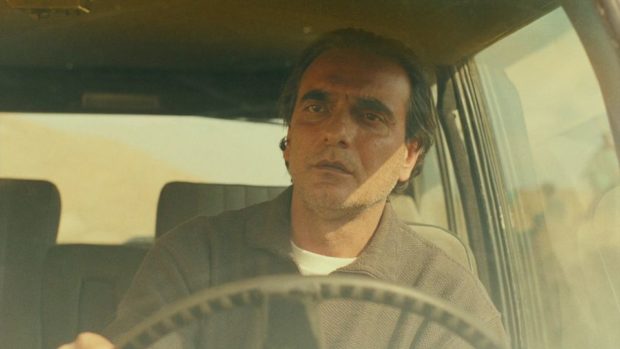

On the afternoon of a holiday, Mr Badi, a man in his fifties, gets out with his Range Rover and drives through the suburbs of Tehran, located on the mountainous heights of the city. The man is desperately looking for someone who would be willing to perform a rather special task for him, and who will not run away from his request, in exchange for a reward.

In the course of his quest, destiny will then gather three passengers who will sit in his car : a young soldier on leave, followed by a theology student, as well as an old taxidermist. Each one reacts to his proposal in a different way…

AN ATYPICAL PROLOGUE

From the pre-generic of his film The Taste of Cherry, Abbas Kiarostami expressly plays on the mystery by introducing the viewer to a stranger at the wheel of his car, which revolves around a traffic circle besieged by workers. For long minutes, and without ever expressing anything, the character obviously seems to be looking for someone or something. Thus, this beginning of the film constitutes a real dynamic for the spectator, notably because of its double tension : on the one hand, the mysterious quest for an enigmatic character, and on the other hand, the questioning of the motives for this quest.

It is finally on territories under construction and isolated from the city that the protagonist takes the floor to accost the few men on the road. He seems to be driven by a paradoxical desire for isolation and « arrangement », that means the spectator witnesses the feverish wandering of his quest towards « the other, » without a definite object. By leaving the hypotheses open about the driver’s quest, Kiarostami, in this way, brings into play everyone’s unconscious.

Metaphorical language being characteristic of Kiarostami’s work, the omnipresent mystery in this prologue thus invites us to think more about the importance of the image, its metaphors and implicit meanings. The landscape, for example, reflects the protagonist’s state of mind, and the vast deserted expanses reinforce his sense of isolation and loneliness. Finally, the uniqueness of the prologue lies in our ignorance, and in the enigmatic personality of the character who runs behind a mysterious motive, revealed in the second part of the film.

A REVEALING AND DECISIVE SECOND PART

Behind this scheme of the man in the car, Kiarostami is inspired by the mystical poetry of Iran, in which the idea of an initiatory journey towards fulfillment is fundamental. The car shows an openness to the world, and if Kiarostami’s cinema is known for its use of symbolism, the notion of a journey and zigzagging paths translate the idea of the path of human existence.

The protagonist is going to make three decisive encounters in turn, during which he is going to explain his identity, but above all the object of his quest.

Mr Badi’s first encounter is with a young military who is trying to reach his barracks. This sequence almost takes the form of a kidnapping : barely settled, the timid Kurdish soldier finds himself next to a talkative and intrusive Mr Badi. The climax of this situation is reached when the young soldier has to return to his barracks, and Mr Badi makes a detour to take him to the heights of the city, pretending to go for a walk. Once there, he presents him with the hole he has dug, and explains his project as follows:

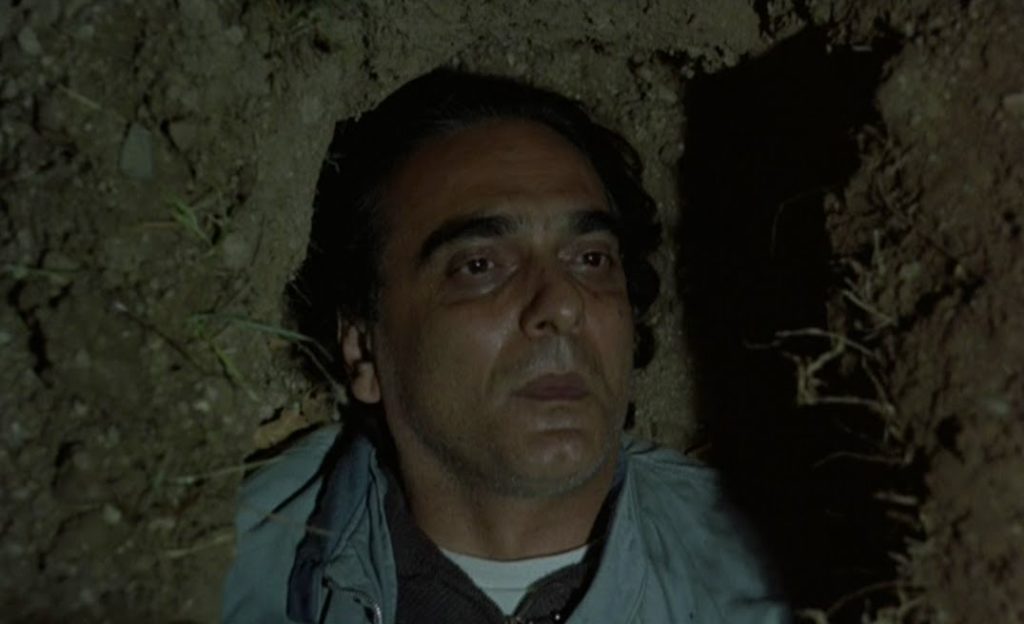

« You see that hole ? At six o’clock in the morning, you come here, you call me twice ! If I answer, you take me by the hand to get me out of there. There are two hundred thousand tomans in the car, you take them and leave. If I don’t answer, throw me twenty shovels of earth. You take the money and leave. Right now I really need you. The man you throw dirt on will no longer be alive. Think that you are farming, you are a farmer and I am manure that you are pouring at the foot of a tree ! »

Mr Badi

The young Kurdish soldier

Despite Mr Badi’s pleas, the young soldier refuses to be an accomplice to such an act and flees.

Later, a theology student of Afghan origin accepts to get into Badi’s car out of loneliness ; but when he learns of his suicide project, the young theologian tries to reason with long sermons, which seem to be ineffective on Badi, who continues to retort :

« I know that my decision goes against your belief ; you believe that God gives life and takes it when it is needed. But there comes a time when man is pushed to the limit. I have decided to free myself from this life. I ask you to act as a Muslim and help me. I know that suicide is one of the deadly sins, but not being happy is a great sin too. When you are not happy, you hurt others. Isn’t hurting others a sin? »

While the seminarian defends his position on the basis of general Quranic principles, Badi only takes into account his particular case. Visually, the characters never appear in the same angle, Kiarostami never films them together, and the shots follow one another along opposite axes. Thus, this visual and physical split reflects their divergence of thought, and their dialogue leads to a point of no return…

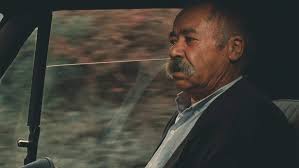

However, against all odds, a miraculous encounter with an old taxidermist of Azeri origin occurs and marks a real turning point in the film, since he is the only one who agrees to make Mr Badi’s decision effective. From this encounter, the film changes tone and the choice of landscapes and images is a true ode to life : just a few shots are enough to recall the beauty of the sky, the sound of the water, and to praise the « taste of cherry » that will perhaps bring the hero back to life. The old man’s story is unexpected, and is in itself a true plea for life:

« The world is not as you see it. You have to be optimistic. Have you ever looked at the sky when you wake up in the morning ? Don’t you want to see the sun rise ? (…) Do you want to deny everything ? Do you want to do without all this ? Do you want to do without the taste of cherries ? Don’t do it, I’m asking you, I’m your friend, but if you want to do it, do it ! »

Visually, the rythm of the film becomes faster and the soundtrack more charged, whereas it was characterized by the slowness and wandering of the character. As soon as this decision is made and the certainty that he is going to die, the action accelerates. Badi’s quest is over and he is now at the foot of the wall of his suicide project. In the end, wasn’t the character looking for the other in his encounters, as arguments that could convince him to stay alive?

In these circumstances, Kiarostami’s work is a kind of initiatory journey in which Mr Badi discovers his true identity. Two solutions are offered to him : either he will succeed in exorcising the idea of death and will come back to life, or he will die.

AN OPEN END

The story told by The Taste of Cherry ends without any real conclusion. Is Mr Badi really dead, or is he still alive? This is a dilemma that remains unresolved, since the ending itself does not tell us what happens to the character, who nevertheless appears on the screen lying in this open-air tomb.

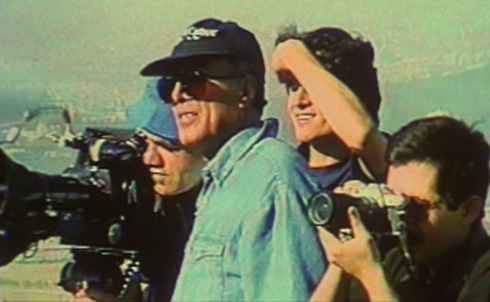

However, the film is not finished. This final sequence goes through a daring transition : a long moment of total darkness, followed by another video that has nothing more to do with the previous image, from a visual point of view. This is the climax of the open ending, as the viewer is taken elsewhere. In fact, the filmmaker Abbas Kiarostami appears in the image directing the filming, and then the actor Homayoun Ershadi, who plays the role of Mr Badi, also appears.

This unusual final sequence gives the film a new movement, and appears as a form of resurrection ; after total darkness, it is the appearance of a new life, another time.

« This little postscript is like an amateur film, a family film shot on video, in an atmosphere of intimacy, as if we were filming life. (…) This open ending leaves room for reflection, and we must believe in an art that seeks divergence between people, rather than convergence where everyone would agree ».

If I shot the final part on video, it’s so that I wouldn’t be forced to continue this story of deciding whether or not man was alive. For me that’s not important. I suppose in principle he should have died, but maybe he was saved the next morning. »

Abbas Kiarostami

• • •

Thus, although The taste of cherry tells the melancholy story of a man who has lost the taste for life, it is nonetheless a work where poetry, philosophical reflections and spectacular shots of infinite, metaphorically charged landscapes are intertwined.

Far from making an apology for suicide, Kiarostami, in the same way as the poems of the great Persian poet Omar Khayyâm (11th-12th century), makes his work a constant praise of life, with an omnipresence of death. As with the poet, death serves the filmmaker to capture life.

Moreover, Kiarostami seeks to testify through his film that life goes on, whatever happens. Thus, it is not insignificant if this final sequence that closes the film makes one think of Khayyâm’s poetic fragment about vanity and effacement:

« Oh, that time when we will no longer be, and when the world will still be ! There will be neither fame nor trace left of us. »

Omar Khayyâm

In tribute to Claire Mercier.