Mariam Tafsiri is a British-Iranian illustrator, who draws her main inspiration from her Iranian heritage, and especially from Qâjâr art, established by the Qâjâr dynasty that ruled the Persian Empire from 1781 to 1925.

In this first interview of our « Civilization » category, Mariam Tafsiri talks about her creative process and her personal relationship with cultural heritage.

BACKGROUND & TECHNIQUE

• Hello Mariam ! To begin with, could you tell us about your background and how your passion for drawing came about ?

I’m a British-Iranian illustrator and economist from London, creating art principally inspired by Persian miniature paintings, Qâjâr art and Islamic designs.

I’ve loved drawing for as long as I can remember really and it was something that was encouraged when I was young. My dad used to have a big holdall filled with paints and craft materials and we used to mess around with that every Sunday (my dad would call it Art Attack for those who know the famous British TV show !).

I’ve always drawn portraits in particular, often using graphite. It’s difficult to pin down exactly why but I’m mostly drawn to images of people.

• In parallel to your work as an illustrator, you are a full-time economist. How do you manage these two activities ? Do you plan to devote yourself one day to illustration only ?

I’m not going to lie, it can be difficult sometimes as there’s a lot of administrative work that comes with being an illustrator and that can be tiring when you’re also working full time. But I started doing illustration as a way to have a creative outlet so I really try to focus on enjoying the creative process.

The most important thing for me is that I get fulfillment out of both my art and my day job – they’re very different but that’s the point. Society is always very keen to put people into boxes so that it’s easier to make sense of them but we’re only limiting ourselves by doing this. So I hope to continue doing both in the future.

• What materials and techniques do you use to create your illustrations ?

I do all my work using the Procreate app on an iPad Pro.

• Your art is really unique and recognisable at first glance. How would you describe it in a few words ?

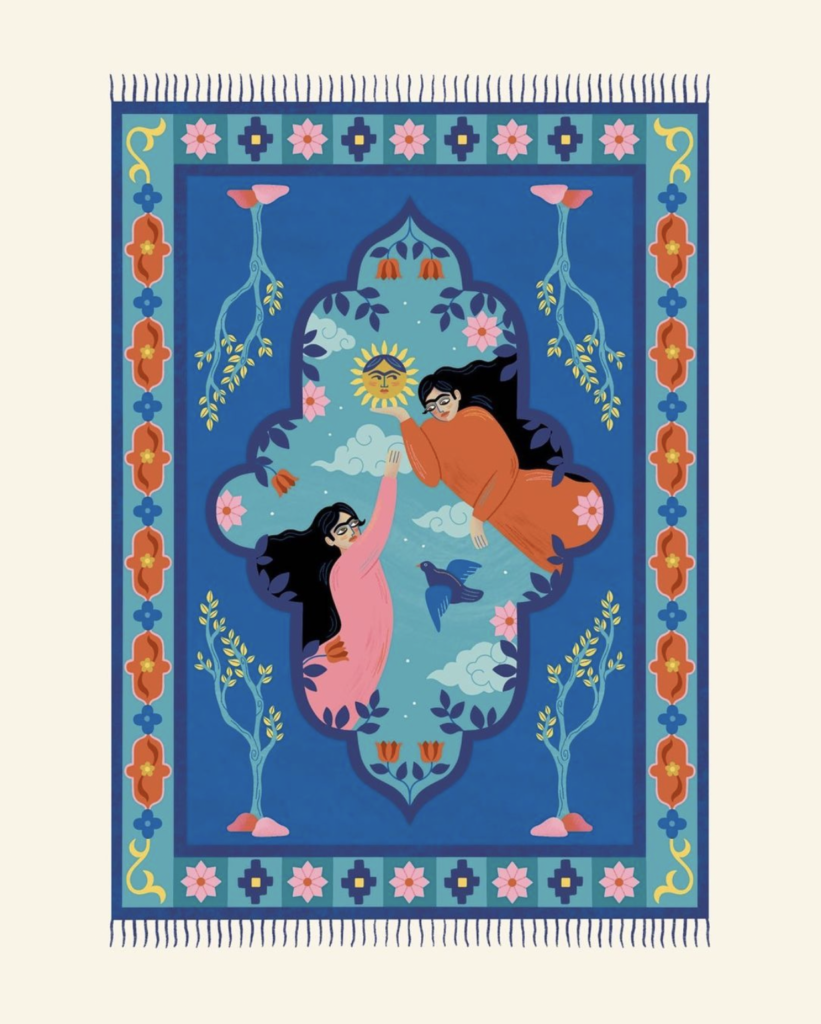

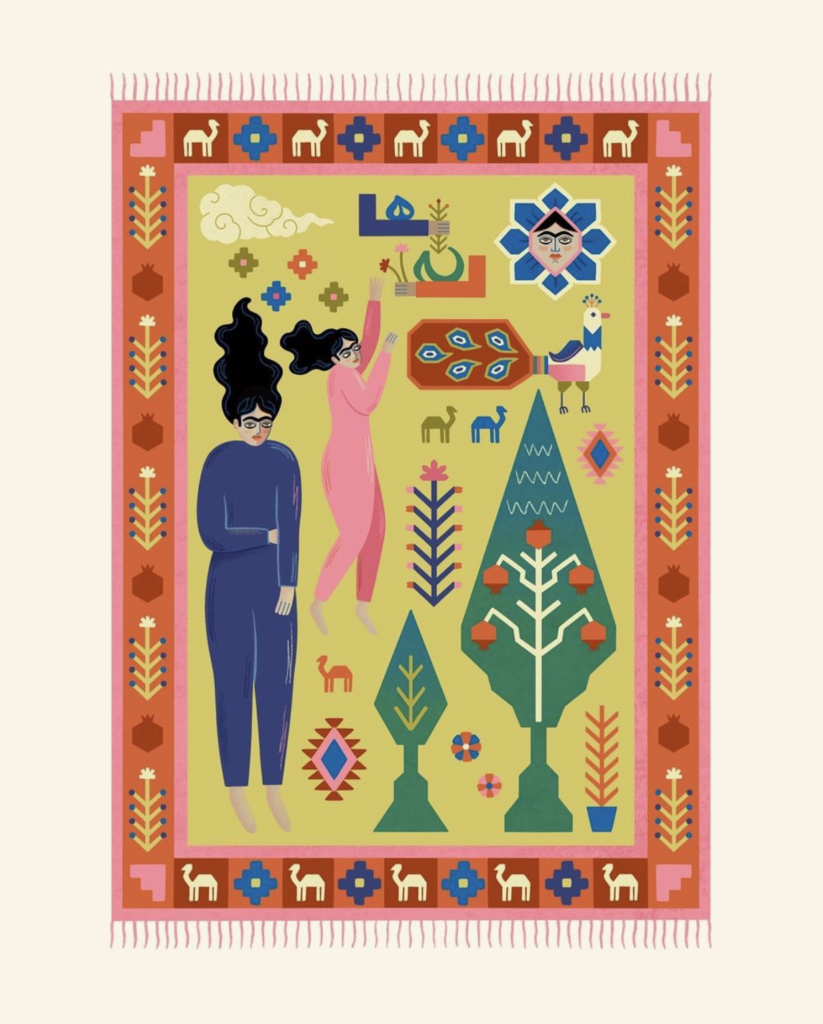

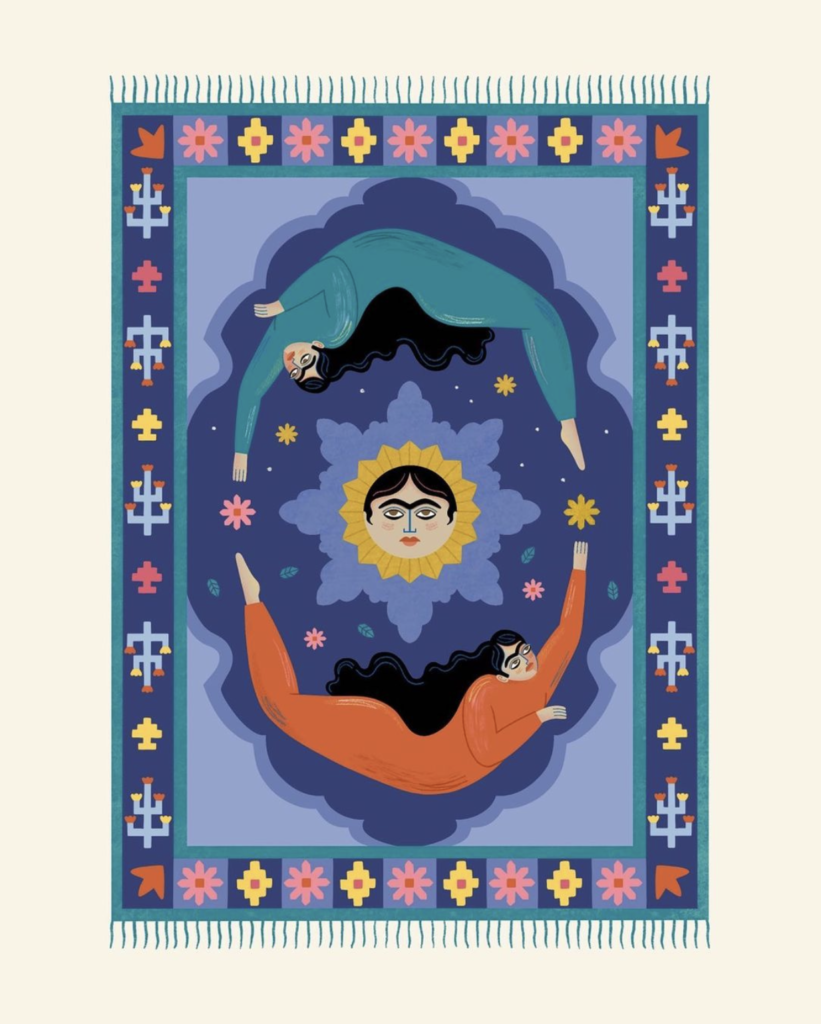

I would describe it as a modern take on Persian miniature paintings, with a central unibrowed character, in a colourful, graphic, minimalist style.

MARIAM AND THE ART OF THE QÂJÂRS

• Your Iranian heritage is central to your work. As a British-Iranian artist from London, what place does Iranian culture have in your life and work ?

As a second-generation immigrant, my family is of course still steeped in Iranian culture and it’s a big part of who I am, whether it be through the food I eat or more subtle things like my sense of etiquette.

I’m a born and bred Londoner so I come from a city where different cultures have been naturally woven into the fabric of society. When I first started following artists on Instagram, I began to come across Middle Eastern artists who created work which made me feel comfortable in my own skin. I was really inspired by that and wanted to express myself in a similar way through art.

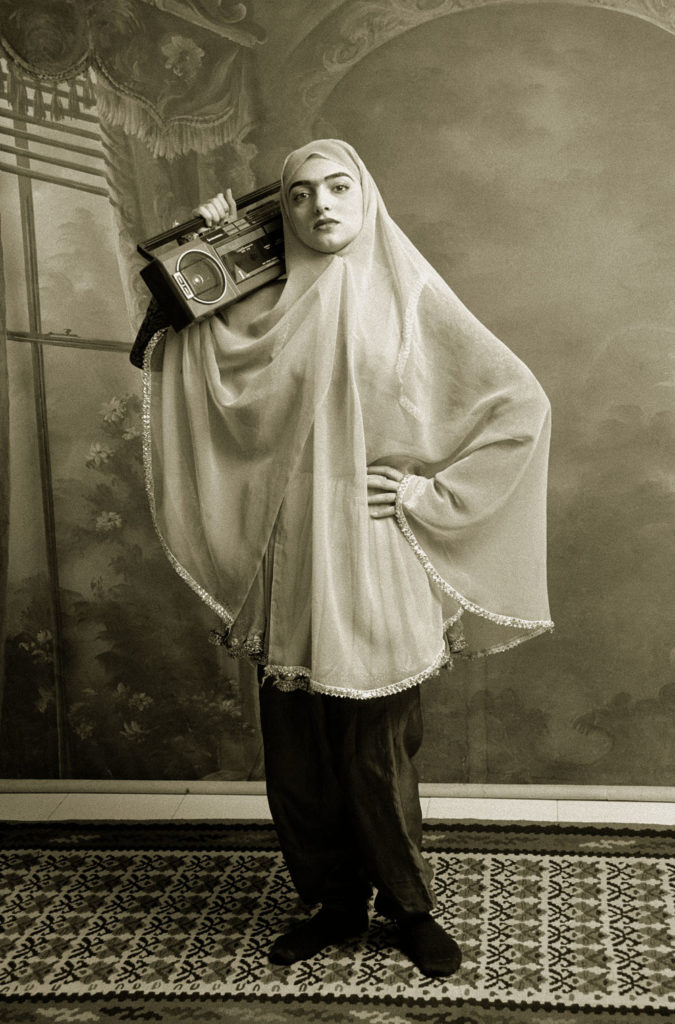

• Qâjâr art in particular, established by the Qâjâr dynasty that ruled the Persian Empire from 1781 to 1925, is one of your main sources of inspiration. How is the art of this period particularly inspiring for an artist (we also think of the photographer Shadi Ghadirian and her photographic series « Qajar » made in 1998) ?

I think one of the most fascinating things about Qajar art is how it combined traditional Persian art with more European styles and techniques. You can see the influence seeping into Iranian art as a result of Iran’s diplomatic and economic relations with European nations. Some examples of this are portraiture or decorative elements (like florals or urns) and all painted in a more realistic style (whereas Persian art has tended to be quite flat in style). But you can still see the Persian twist – using European painting styles and colours but creating individuals in very idealised forms (much like traditional miniature paintings).

Shadi Ghadirian, Qajar Series. 1998

Taj Saltaneh, Naser al-Din Shah’s wife. ca. 1900

I would also mention two other things. For Iranians, Qâjâr imagery is so common and widespread as decoration on items, you just take it as given and don’t think very much about it. Presenting a twist on it makes the viewer think again about what that art represents. For others, particularly in the West, Qâjâr imagery can be quite shocking – you only need to see the reaction to the viral Princess Qâjâr meme…

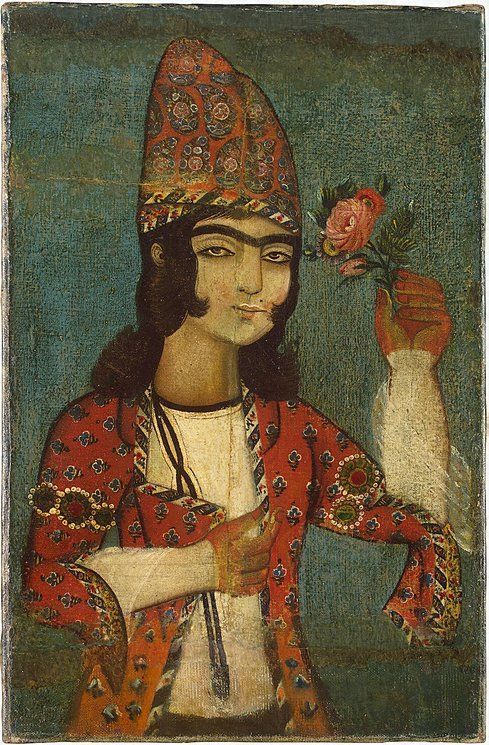

• One of the specificities of Qâjâr art is to blur gender identities of people. Male or female, it is sometimes difficult to distinguish them. Is it an ideal of beauty that you feel connected with ?

Popular media has very clear opposing definitions of masculine and feminine ideals, but this is only one conception of beauty (and more often than not, a very white conception). What is really interesting about Qâjâr art is that it seems to reflect a singular standard of beauty regardless of gender, universally prizing thick locks of black hair as well as facial hair. Such a conception of beauty is so alien to much of society today.

Qâjâr painting.

• Speaking of ideal of beauty, in the same way as in Qâjâr representations, your characters have long black hair, a matte complexion and a single eyebrow. By presenting such physical characteristics, is it a way for you to go against the beauty canons that are the norm today ? It reminds us of the work of the German-Afghan artist Moshtari Hilal who, with her « Tribute to Black Hair« , celebrates the diversity of bodies, hair and big noses in particular.

Yes, absolutely. As I mentioned above, popular media is saturated with a particular version of beauty. It’s so cemented in our consciousness that we forget that beauty standards are ultimately subjective and change over time. Not even just in terms of differences across cultures, but evolution within cultures themselves. For example, larger women often used to be seen as more beautiful, as it reflected wealth and fertility. It’s very difficult to break out of this mindset – this is why I found Qajar imagery so confusing when I was young.

Moshtari Hilal

RECOGNISING IRANIAN TRADITIONS

• Beyond Qâjâr art, other features of Iranian culture and art appear in your illustrations. This is particularly true for Persian poetry, excerpts of which appear in some of your works. Who are your favourite poets, and how do you choose these extracts ?

I love to use poetry excerpts as I find it a lot of fun thinking of how I can depict the message through illustration. It really encourages you to think creatively – it gives you some guidance and structure but at the same time lets you be very free with your imagery. Poetry is also very embedded in Iranian culture, more so than in other cultures, so it seemed natural to bring that into my work.

I think my favourite of the famous Persian poets is probably Saadi as there’s often a social and moral side to his observations. In terms of choosing the extracts, I find some immediately spark imagery in your mind so are most suited to translating into illustration.

• Your illustrations offer a very colourful palette and present rather minimalist and uncluttered settings. Various symbolic elements recur in them, such as certain colours, the moon, the sun or pomegranates. Do you attach great importance to symbolism and metaphors, which are widely present in Persian poetry ?

I like to look through historical artworks to understand the different imagery and symbols which are often used as I then take that over to my work. It lets me give a nod to these works without creating pastiches. My works can be quite surreal or whimsical and I enjoy using such symbols to that effect.

• In some of the illustrations you can also see the influence of Persian miniatures. Is this an art form that you appreciate ? Which miniature artists or works in particular touch you ?

Definitely – as I mentioned earlier, I’ve always loved art which depicts people and people’s lives. But what makes Persian miniature paintings stand out for me is the way they capture people in very free-flowing positions and tell a story. This is very different to European portraiture which was an art form designed largely to boast of the sitter’s wealth.

I’m also inspired by the way miniatures often spill outside their borders (as if breaking that fourth wall) and also by their use of bright colours. One piece I particularly love is the horoscope from “The Book of Birth of Iskandar”.

• Through your art, you also contribute to the recognition of Persian customs and celebrations. For Nowruz, the Persian New Year in spring, you have created “stickers” on Instagram. You have also created works related to Shab-e Yalda, the celebration of the winter solstice, and you regularly highlight characteristic elements of Iranian culture : pomegranates, tea or carpets. Are you proud to participate in the recognition and enhancement of these traditions ?

It’s difficult coming from a Middle Eastern or Muslim background and forever being associated with negative imagery. So part of my work is about sharing the beauty and history, but in a personal way. As with poetry, Iranian celebrations also come with a lot of symbolism and that provides me with a very fun brief to develop an illustration.

• As a contemporary artist, do you feel it is essential for an artist to draw on his or her historical heritage to create something new and unexpected ? What is your relationship to the notion of heritage ?

I absolutely don’t think an artist has to draw explicitly from their culture or heritage. Identity politics can sometimes push people into silos where they repeat tropes and I really think we need to get away from that.

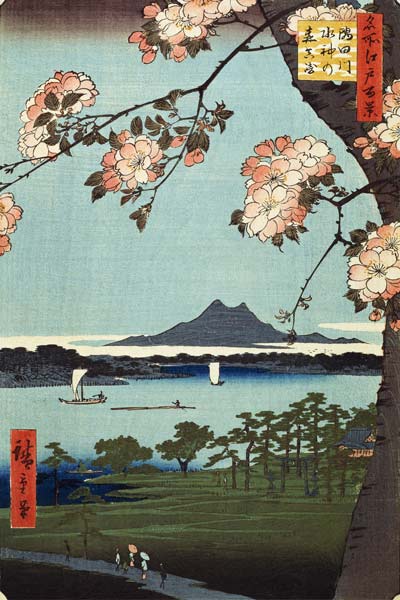

My art is of course shaped by my Iranian heritage but I’m influenced by a wide variety of cultures and histories, from an 18th Century English artist like William Blake to traditional Japanese woodblock prints.

For example, the miniature painting tradition isn’t just confined to Iran – our cultures and histories are all very intertwined. Acknowledging this cultural exchange is important to allow us to move beyond identities defined by modern nation states.

Ultimately, art isn’t created in a vacuum – all artists are to some extent inspired by what has come before them.

OTHERS INSPIRATIONS

• Apart from Iranian art, what are your other sources of inspiration ?

I mentioned a few above like Blake and Japanese artists like Hiroshige and Utamaro. I’m also influenced by 20th artists such as Matisse and Goncharova in terms of their use of colour and simplicity of form. I’ve always been fascinated by history so my art gives me a way of engaging with the past as much as anything.

Hiroshige

Henri Matisse

• It seems to us that you love visiting exhibitions. What are the latest ones that have made an impression on you, and which have perhaps nourished your work ?

The lockdowns have disrupted things a bit so I haven’t been to as many exhibitions over the past year as I would’ve liked. I love to see things at exhibitions and think about how that might make me change my own work.

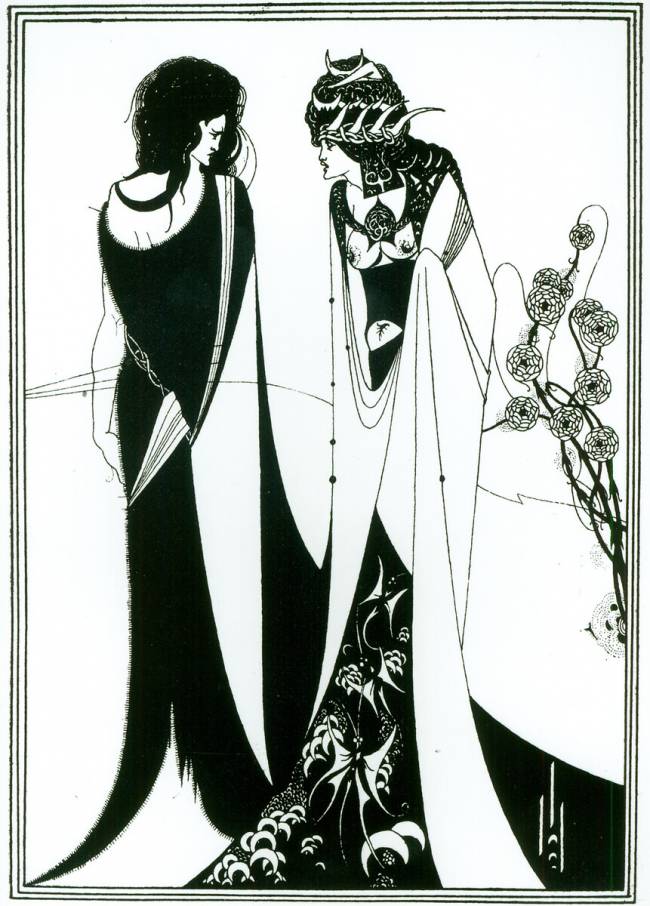

One exhibition I absolutely loved was the Aubrey Beardsley exhibition last year at Tate Britain – his illustrations are just incredible in terms of their detail but most of all the curves and flows in that very naturalistic art nouveau style.

I would also actually really recommend the Tate Modern permanent galleries – they’ve had a rehang since they closed during the lockdowns and they’ve included many more international artists which is exciting to see.

• Finally… Would you like to share a lesson you have learned through your art practice ?

You can learn a lot from things that don’t go as planned. With art, you have to keep experimenting and sometimes the output isn’t something you like. But from that you learn what you like and what you don’t like, what you should do and what you shouldn’t do. And that in itself is invaluable.

IN THE SPIRIT OF MARIAM TAFSIRI

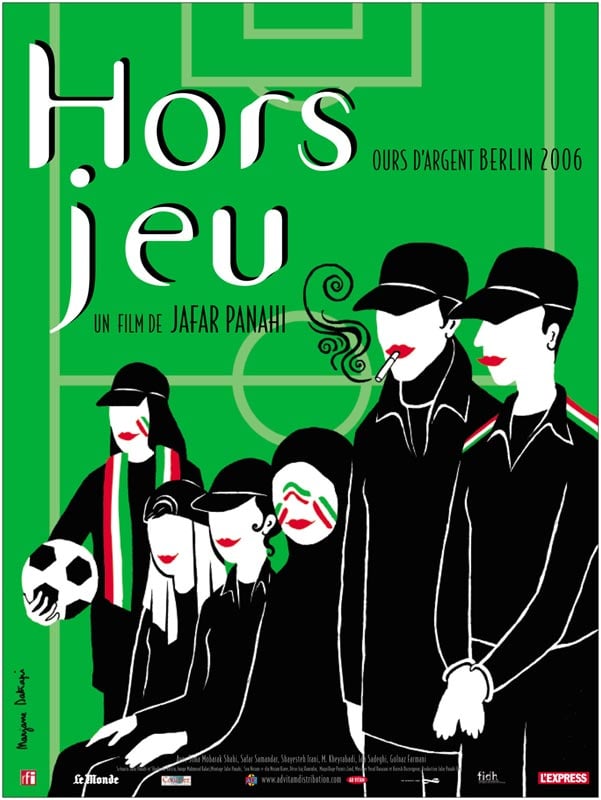

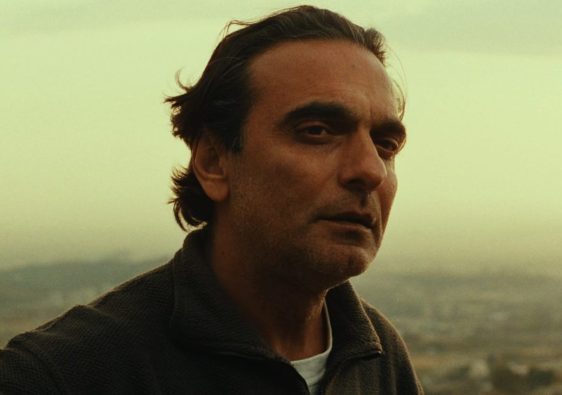

A movie ? Offside, by Jafar Panahi (2006)

A book ? One Hundred Years of Solitude, by Gabriel García Márquez

A painting – an artist ? Monet’s Water Lilies (the triptych at MoMA), by Natalia Goncharova

A song ? Bewitched, Bothered and Bewildered

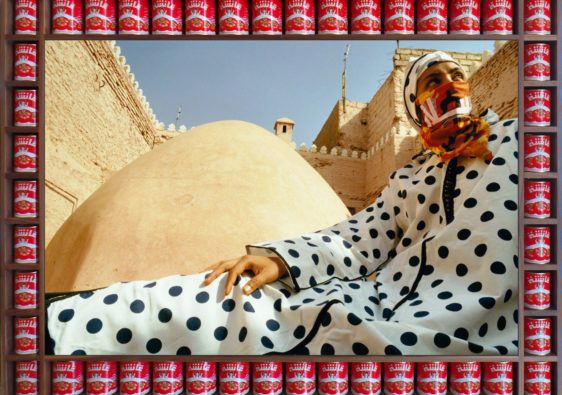

A picture ? Any photos by Eric Van Nynatten

A word ? Cosmos

A dish ? All the kebab

An instrument ? Violin

A place ? London